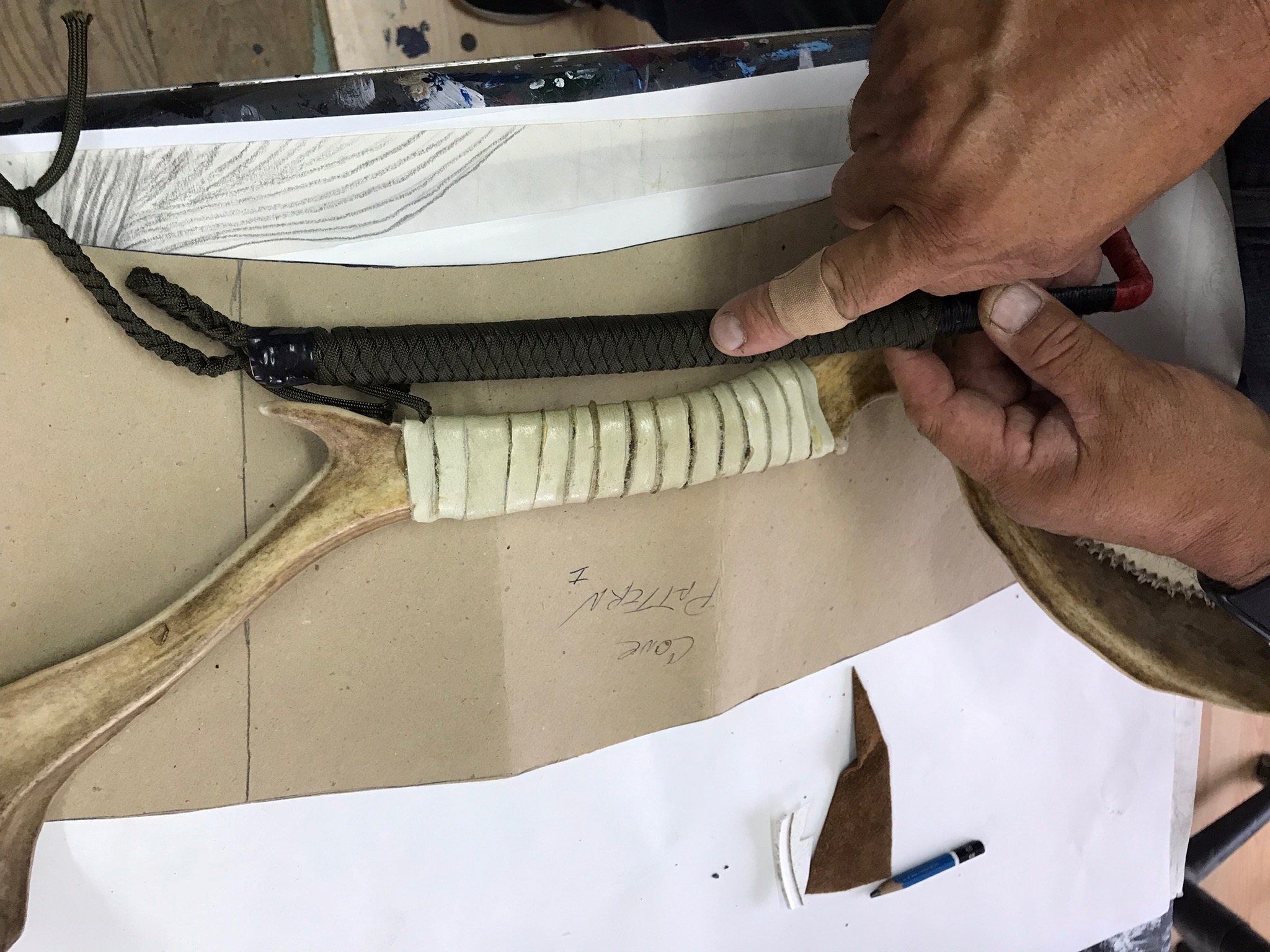

Karl Chevrier, a talented, accomplished contemporary artist and traditional craftsman from the Anishinaabe community of Timiskaming First Nation, compares his practice to birch bark canoe making and “everything that goes with it”. His works of art blend tradition and innovation, carry strong messages and reflect his renewed commitment to causes that are close to his heart, including identity, protection of the environment and mutual aid. Chevrier has a sensitive soul and is proud of his origins. His fondest wish is that his efforts, works and teachings serve as beacons for others who also follow a road to healing. Besides giving lectures and workshops promoting full autonomy, Chevrier opens the door of his workshop to all those seeking to learn : “I can only plant a seed; then it’s up to them to make it sprout, grow and bear fruit.”

For all these reasons, he was named Master of Living Traditions by the Conseil québécois du patrimoine vivant in 2024.

He is also part of the NIN exhibition, an exhibition on the Anicinabe language and culture presented at the Musée de la civilisation.

“When I come back to my own culture, I can strongly use the words of the elders. Artists have always been like sponges: when they hear things, they absorb it. When elders talk, they draw you into their story and, as a visual artist, you can see those words and you can just add on to that and tell their stories: how we got here and how we have survived through the dances, through the songs, through the drums and everything that connects us in that way. [Art] is a way to express who you are as a First Nation. For me, it’s a good healing tool.”]

Karl Chevrier’s first works of art go back to the early 1990s; his artwork rapidly came to public attention. After taking part in several exhibitions and winning a few awards, he attended the White Mountain Academy of the Arts from 1999 to 2002; his joint study of European and Native artistic approaches contributed to nurturing his own reflection on art and his role as an artist. But most of the teachings that had a very significant impact on his life as a person and an artist were received outside the classroom. Learning how to make a birch bark canoe triggered a complex process of self-healing and identity awareness in him.

“When I went back to see the elder [who taught me], I asked: ‘What did you do to me?’ And he said: ‘You were walking blind; I opened your eyes. Now you see nature in the way it should be looked at: beautiful, respectful. Just take what you need and teach that.’ I’ve been doing that ever since.”

According to Chevrier, the greatest power of art is its capacity to express what words just can’t. Art gives those who suffer the tools to address things and matters that haunt them. By performing this subtle role, art contributes to shape tomorrow’s society.

“I don’t seek fame and wealth; what I seek is healing.”

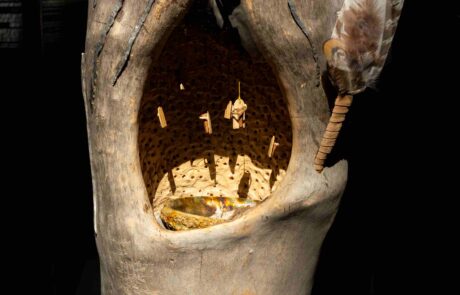

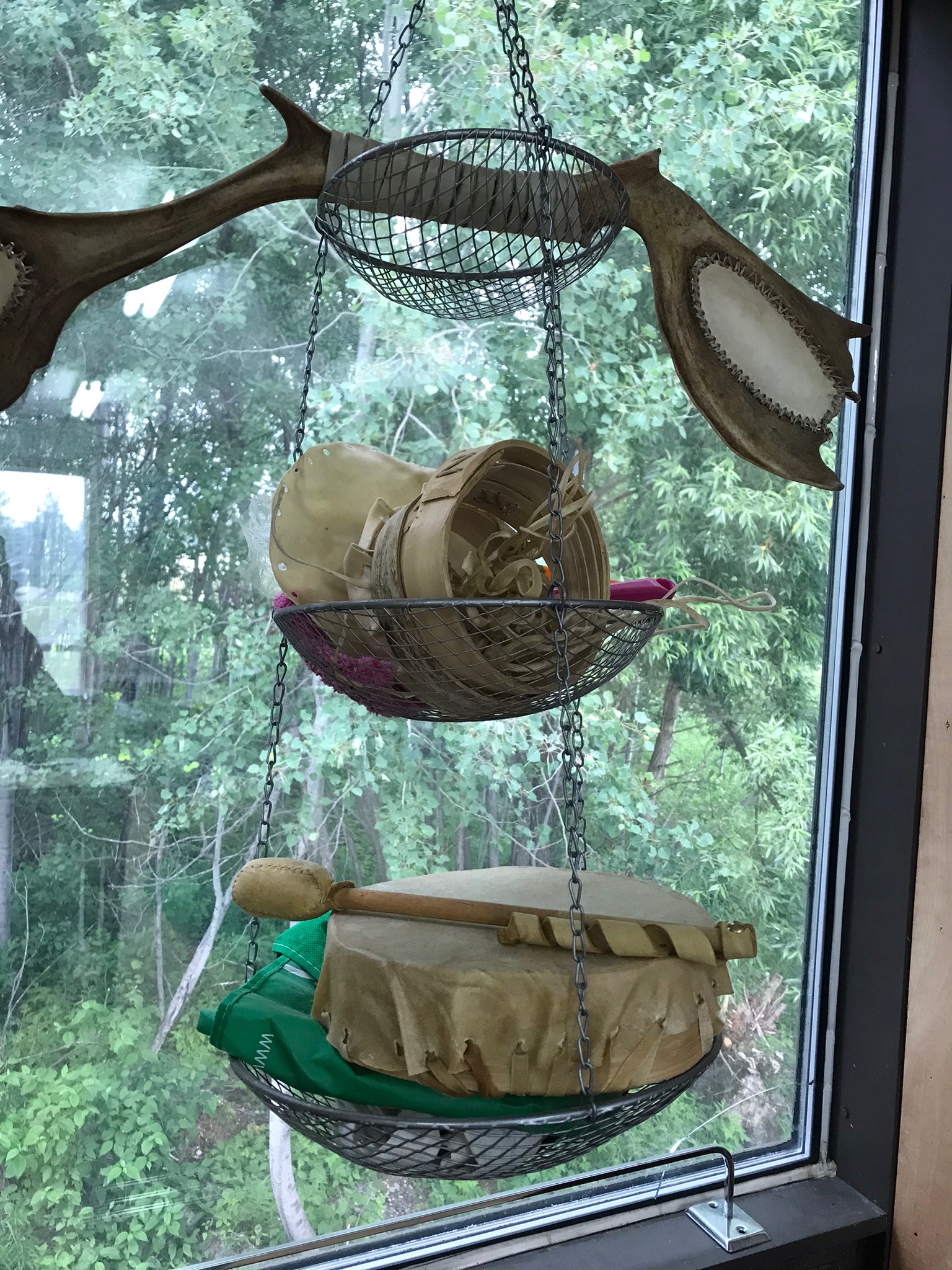

Karl Chevrier comes from a large family in which he developed a sense of care and community. Her mother passed on to him her creativity, wisdom and culture. She was a key figure in his life and the pillar on which he built the foundations of healthy living. His father taught him about life in the forest: hunting, trapping and harvesting raw materials. This man could picture a sculpture out of a simple piece of wood. He showed his son to love the forest for all its potential. When he started out his career as an artist, Karl Chevrier visited dump sites and check waste bins, looking for items he would take back to his workshop in order to give them a second life. The forest plays a similar role in his artistic process: to make a sculpture, for instance, Chevrier goes to a lakeside to collect clay. He likes to work with materials from the environment, for turning them into works of art adds value to them and a chapter to their life. In his opinion, the collection of materials is as important as the making of the work of art, for it is a moment where one expresses respect and gratitude towards the environment. The Anishinaabe values he inherited from his parents and elders are dear to him, and he makes it a duty to convey them to others.

“A tree is no longer only a tree when it gives you the right to harvest its fruits, when it becomes a source of food, or when it can cure you.“

Karl Chevrier discovered a passion for teaching when he worked at the Obadjiwan/Fort-Témiscamingue National Historical Site, Ville-Marie. His job as a cultural facilitator required him to demonstrate how a birch bark canoe is built. Chevrier recalls a day when he was filled with doubts: a young boy, who was visiting the site with his teacher and classmates, made it clear that what Chevrier was teaching was much more than skills. The boy walked to his teacher and asked: “How do you explain that our story books do not talk about respect, canoe making and all of these teachings?“ The boy’s question left Chevrier speechless; he suddenly realized the full impact of his work on young people and showed him the path he is still following today. In 2014, Chevrier started giving lectures in schools, in which he shares the challenges and successes he has encountered in his life. He also welcomes groups in his studio to teach art by experience. He hopes to impart values and attitudes that can help young people build a healthy life and make enlightened and conscious choices. As he puts it, this is a question of ensuring the health of our society and the environment upon which all life depends.

“It would be a better world; it would be a better life and there would be less fighting [if Natives and non-Natives could stand together]. This is what I think of when I do my work: we should always be able to see seven generations ahead of us, but we only see this far. Make a stand now and fight for your future generations coming up. Everybody has a role to play; mine is to create and design, and I hope my work will speak to people.”

Proud of his culture, Karl Chevrier travelled to Brussels in 2023 to represent the Anicinabek nation at one of the world’s biggest Christmas markets, Plaisirs d’hiver. He also took part in the NIN exhibition, which toured Anicinabek communities to meet young people. In addition, as part of the Odeimen project, he produced a unique wood sculpture on display at the CISSS of La Sarre.

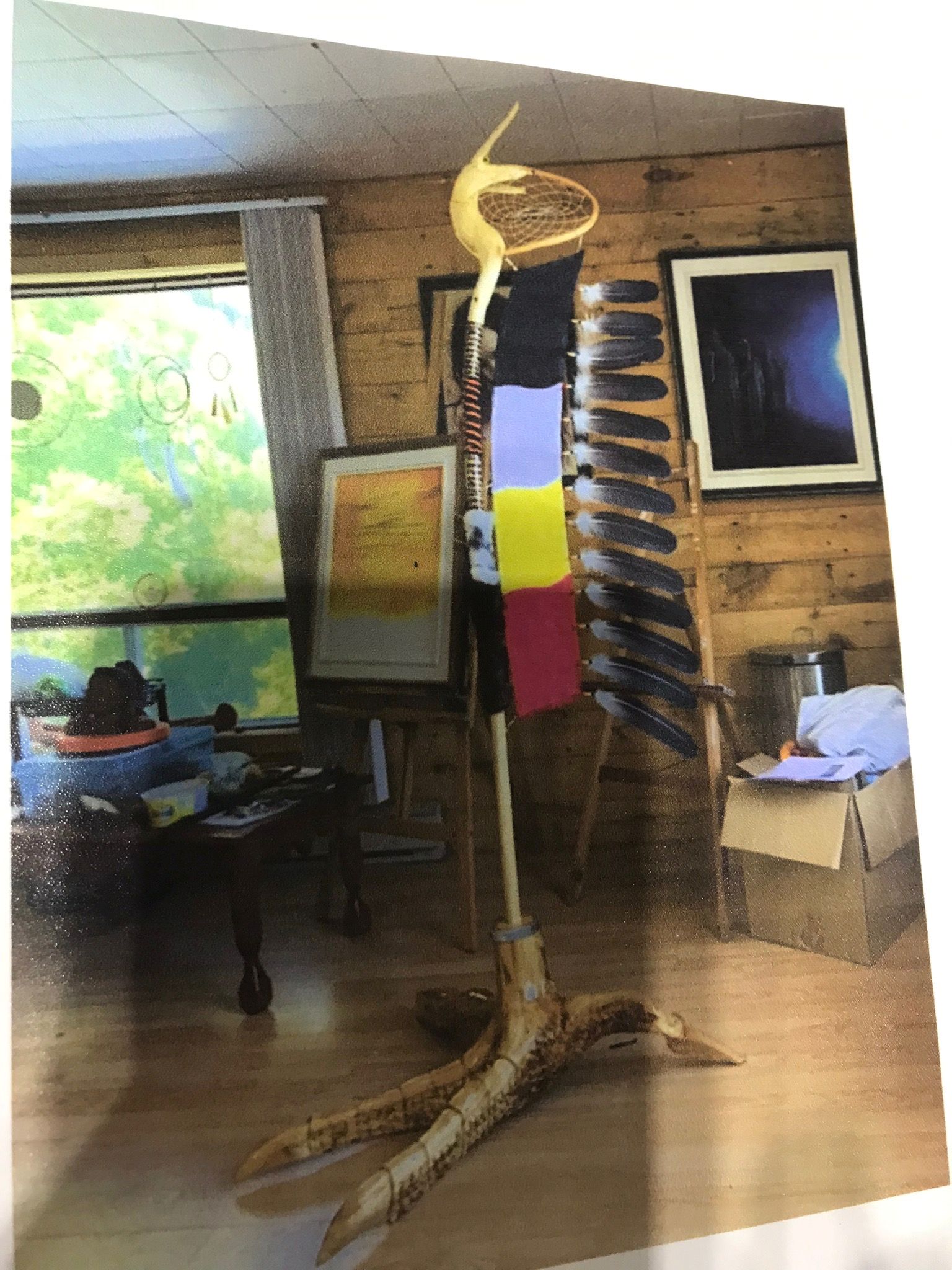

Karl Chevrier presents his sculpture project for the TFN community: a traditional jingle dancer (2016)