All his life, Richard Kistabish has been committed to defending, body and soul, the rightful recognition of his nation, but above all, he has paved the way towards the search for innovative solutions. At the local level, he was president of Minokin Social Services, and served as director and manager of the Kitcisakik Community Health Committee. He has also worked in the health and social services field at the regional and provincial levels for many years. Gradually, he has become a strong voice in his territory. He was elected Chief of the Abitibiwinni First Nation community and then Grand Chief of the Algonquin Council of Western Quebec for two terms. He later chose to withdraw from politics to become more involved in concrete action with indigenous communities.

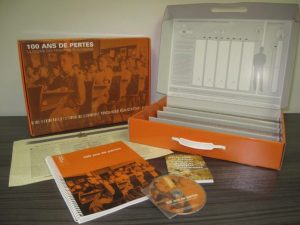

The residential school issue has always stuck to him, as he himself was forced to live in such school for 10 years. Therefore he did not hesitate when the federal government offered him to sit on a board of directors dedicated to the management of compensation funds granted to implement healing processes in various communities across Canada. Ejinagosi was responsible for reviewing and analyzing projects promoting alternative means such as traditional healing. As part of the project, he developed an educational kit to help students of all ages and nationalities understand the impact of residential schools on First Peoples.

“With some dignity regained and pride resurfacing, I am very happy to still speak my language.”

He dedicated several decades of his life to exposing the abuses committed in residential schools. He is currently the President of the Legacy of Hope Foundation, a charitable organization active in raising awareness and educating Canadians about the residential school system and its intergenerational impacts. Each action of this foundation reflects the will of its president: that of finding ways to achieve collective healing. At Mr. Kistabish’s initiative, the Foundation has documented and shared the stories of 800 residential school survivors. The idea behind this approach was not to let these testimonies fall into oblivion and also to provide essential elements of understanding for the generations that followed and suffered the indirect impact of these deep wounds.

“In 1975, I made a personal commitment to make known the history of residential schools. I also wanted to make sure that this kind of experience would never happen again across the world. It should never happen again. Never, at any time.

I committed to taking every opportunity I can to make this story known. It was my commitment, the battle of my life. That is what made me stand up. It is what led me to assume my responsibilities, my duty, my obligations.

I wanted to make sure that the necessary changes were made to correct this. This was the most fundamental part of my approach. I think I received the necessary gifts to do so. Indeed, I was already raised to be a storyteller when I was very young. I used that gift to pass on that story to others.” (excerpt from an interview conducted by the School of Social Work of the Université du Québec à Montréal)

He therefore had a strong impact on the history of the Anicinabe and other nations in Canada, as these interviews served as an important basis for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. It is based on this Commission’s report that, in May 2015, the Supreme Court of Canada described the impact of the residential schools as a true cultural genocide, thus forcing the federal government to acknowledge its responsibility and invest in reconciliation efforts. Ejinagosi’s efforts to carry out this colossal project of recording testimonials earned him the YMCA Peace Medal, as well as the Coup de cœur award from Bâton de parole, an organization that gathers and disseminates all the indigenous news from Quebec, Canada and the United States in order to link various communities. He has also been invited several times as a speaker or panellist at international conferences. His last two lectures addressed the issue of language.

Ejinagosi is now the president of Minwashin, an Anicinabe cultural and arts development organization. With a board of directors made up entirely of members of his nation, he advocates, promotes and transmits Anicinabe culture and is committed, since the organization’s inception, to the protection and revitalization of his indigenous language. His social and political involvement, which has always been an important part of his agenda, continues to be a major part of his life: he is also President of the Legacy of Hope Foundation, which is dedicated to raising awareness and educating Canadians about the residential school system and its intergenerational impacts.

Having lived through ten difficult years at the St-Marc residential school, the education of Anicinabek children in their language, immersed in their culture and surrounded by their families, quickly became an important issue for Richard. While he was chief of the Abitibiwinnik, he was instrumental in bringing school to the community so that children would no longer have to leave their families to study in Amos.

“It seems to me that we are lost. And it is not necessarily a simple loss of land, but it is also the loss of our souls. I call ourselves the seriously burnt souls. We have become scorched souls. There exist medicines we can take to heal our souls, there are approaches that must be used to try first to sooth the pain and then provide continuous and appropriate care. There are many ways to do this.”

In this interview, Richard talks about his experience at the Saint-Marc-de-Figuery Native residential school.

(“Peuples autochtones de l’Amérique du Nord.” © 1982 TÉLUQ — l’université à distance de l’UQAM)

Richard is respected for his indomitable outspokenness, but also for his wisdom and unwavering dedication. Words are lacking to faithfully translate the thirst for justice and humanism of this man with an astonishing background. His vast experience has given him an acute knowledge of the issues affecting Canada’s indigenous peoples. Even today, he remains closely connected to the daily realities of the Anicinabe communities and is at the forefront of language revitalization in the territory. His experience of healing processes through cultural and identity revival provides him with a holistic view of the issue of traditional languages.

“When I try to find a word for ‘hope’ in my language, I say ‘kadaminokijikanniganwede’: ‘it has to be sunny ahead’.”

Often against all odds, Richard was able to surround himself with strong allies and mobilise key players from different backgrounds. He has initiated countless administrative reforms and partnerships that have had a concrete impact on the lives of his people. In recent years, he has turned his attention to the future of the Anicinabe language. The transmission of Anicinabemowin to future generations is now a major concern for him. With the Minwashin organization, he has created an annual event, Miaja, a gathering of all Anicinabek communities in Quebec and experts from other nations around the revitalization, enhancement and transmission of Anicinabe heritage, arts and culture. The 2019 gathering focused on language and was the culmination of a series of actions to mark the International Year of Indigenous Languages and to sound the alarm about the urgent need to act for the survival of Anicinabemowin: audio and video recordings of the territory’s unilingual Elders, support for community radio stations, educational kits with labels to help learn Anicinabe words, and more.

Recently, Minwashin brought together the Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue (UQAT), the Faculty of Education of the University of Ottawa and the Living Lab in Open Innovation in Rivière-du-Loup to create a social innovation laboratory that will work with communities on concrete actions that can be implemented for language revitalization.

For decades, Ejinagosi has lent his voice to a nation that is still known as the “invisible people”. His dedication has brought new visibility to the Anicinabe people through the implementation of innovative projects. To have an Anicinabe sitting on an international working group would be a source of pride for the entire nation and proof that the years of silence and invisibility are a thing of the past. Richard is an Anicinabe symbol of resilience, like many people in his nation, but he is also a strong political figure and a man of action.

“They used every means to stop us, to make us disappear. They used our culture, our spirituality, our language to make us disappear. So the only way we can put ourselves back in place, to find ourselves again, is to revive the practice of our culture and language as well as to celebrate the way of life of our ancestors, and that takes a lot of resilience.”

Through the story of the first years of his life, by the Harricana river, and the legend of the birch tree, Richard shares his culture and vision of life.

(Directed by Dominic Leclerc)

Des générations successives d’Autochtones ont souffert, pendant cent années, de la perte de leur culture et de leur spiritualité suite à leur passage dans les pensionnats indiens. Par le biais de cette conférence, vous serez informés du contexte historique à l’origine des problèmes sociaux actuels auxquels un grand nombre de Premières Nations, d’Inuits et de Métis sont confrontés. Il est important de valoriser et de stimuler des discussions plus approfondies et des enseignements afin que les Canadiens puissent cheminer avec les Autochtones pour parvenir à la compréhension mutuelle et à la réconciliation.

Clientèle : 3e cycle primaire, secondaire, enseignant

Durée : 1 h

Educational program

The Legacy of Hope Foundation created an educational kit for youth aged 11-18.