Nin

I am

Je suis

Anicinabemowin ka apitendjigadek enisidjigan

Owe keko mitasopipon nikan, anishinabe icikicwewin kata kanwapitcikate. Kitci nakickotatiek ka otci ocitcikatek “NIN” ka icinikatimak. Ki mitonentcikate aninabemowin. Ki ocite ocitcikanan, atisokanan, weckatc Anishinabek o pimatisiwina, aki otci.

Ka ockinikiatc tapickotc apinotcicak kitci nisitwenamatc weckatc pimatisiwin, eka kitci wanikewatc ati e otcimakak, kitci minentamatc e anishinabewiatc kiapatc. Nanan kekonan kata takwatcikate, kitci kanwapitcikatek masinaikanikak, masinatesitcikanan konotc ocipiikanan, kitci notcikatek, kitci takinikatek anishinabek otapitcitawina.

AN EXHIBITION THAT HONORS THE ANICINABE LANGUAGE

At the beginning of the International Decade of Indigenous Languages, the Nin exhibition is a place to meet and reflect on the issue of revitalizing the Anicinabek language.

Nin is a nomadic exhibition designed to share the worldview of the Anicinabek people and to foster interest and pride in their identity, language and ancestral heritage among Anicinabek youth.

The exhibition is composed of five thematic zones that will allow visitors to address certain aspects related to the history of their ancestors, the Anicinabek, their relationship to the territory as well as their vision of the world through the language – Anicinabemowin, which is the pillar of knowledge transmission.

NIN AKI > I am territory

INABIN, NIDITAN, KIDJI TEHIN KA IJA KITCI MICAK ACITC KA MINWACAK.

Anicinabe aki, mi wedi e odiseyak. Mi wedi ka odjisemigak anicinabemowin. Mi keninwit Anicinabe Aki kak e iji tabenidagoziyak tabiskot sagihiganan, sibin, mitigok, awesisak, mindjocak, kitiganan, asinik, pokidinan… Eko apin kitci mitaso mitana pibongagan, aji owe widjigijemidiwin tagon nid anicinabemowinan acitc nid ijitawinan ka iji anicinabewinanan. Mi dac owe e ijinagoziyak.

Observe, listen, TO BE in the vastness and splendour!

Anicinabe aki, that’s where I come from, that’s where we became who we are, that’s where Anicinabemowin originates from. Lakes, rivers, trees, animals, insects, plants, mountains, stones, Anicinabe aki shares them with us. For thousands of years, this relationship has been embedded in our language and culture. It is the foundation of who we are.

Listen to the sound on the territory

MANADJITO AKI

« Kipic kowatc mitik, kakina abidjihagani. Mitokokan e minigowin kegon, kegin ki mina kegona migwetc kidji inendamiwin. Tcimankewin kakina kiga mikan pecotc wakahi : wigwas, odibi, mackikwatik pigiwo, kickadik, anitimik… kakina tagon. Kicpin ickwa abidjitowin kakina kigiwe pagidinan kagi odapinamin. »

– Karl Chevrier

Manadjito aki, odapinan eta ke inabidjitowin kidji odji madjiwin. Kidji kikenidamiwin anapitc ke anikiwin kidji pagidanatc awesisak kidji o tcidjimiwatc kewinawa kidji manewatc.

Kidji kinendamiwin owe tabiskotc apitendagosik owe anicinabe aki. Kakina madiziwin inendagozi kidji manadjihaganitc.

Respecting the Earth

“When you cut down a tree, everything is used. The forest offers you something, you offer something in return to express thanks. To make a canoe, you can find everything needed within your surroundings, birch, roots and spruce gum, cedar, ash… everything is there! When you don’t need it anymore, you return it to the forest, you give back what you borrowed.”

– Karl Chevrier

Respecting the Earth means taking only what is needed to live. It is knowing when to hunt the animal to let the reproductive cycle of each species do its work. Preserving this fragile balance of Anicinabe aki is also what it means to be Anicinabe!

The human being is equal to all living beings on this Earth, he is only a part of the whole that is Anicinabe aki. Every form of life is worthy of respect.

NIN AKI

Kiyabitc tagonon kagi iji widamak tajigotc aki kak nac dac ketagok nid aki nan, nid ijigijewinan tagton. Kicpin dac aga tagok anicinabe aki : kawin tagosinon anicinabemowin. Kitci apitenidagon dac owe.

– Oscar Kistabish

Pepejik pejigodenak odiyanawa kewina adi e inabidjitowatc od akiwa. Kakina awec ka ijawatc ogi widanawa (sahiganan, pokidanan, minotikonan, kodigwinana … acitc nin paba ijaman e adisek pibonagak. Manadjiwin acitc kackitowin1. Pekac kidji tcodjominan acitc ki migwaminan, aki miha e odji madizowik acitc kida tebwetaminan. Odanin mayawiwin kida mayawiwainan. E kekogosak dac anicinabe akin ac waswanipiwinik kiwedinok kak nac adikamegok wabinok inekena odjibowek dac cawonok kak. Kawin kida tabinidisinanan aki. Kiniwit ka tabinimogowik aki.

- Ejinagosi, 1986, p. 2

I am territory

“The names [of places] still exist in the territory and as long as the territory is there, our language is there. If our territory disappears: no more language. This is a very important point.”

– Oscar Kistabish

Each family has a special relationship with the territory. Each significant place is given a name (rivers, mountains, islands, etc.) and “[…] we were constantly traveling through it according to the rhythm of the seasons. With respect and efficiency1“. As both our mother and our home, she holds a place at the heart of our lives and our spirituality. Her balance is our balance. From the Eeyou (Cree) territory in the North, to the Atikamekw territory in the East and the Ojibwe territory in the West… The Earth does not belong to us. We belong to it.

NIN MAYAWIWIN > I am balance

NIN MAYAWIWIN

« Ni pabamagimoseman kon kak, agim nida

abidjihanan, tciman acitc. Odibin kak niga mayawinan,

kiyabitc ni nanibwiman. »

– Normand Kistabish

Ka wawiyak mackiki kakina mayawin acitc kakina samipakesin mawadopikesin mi owe ninwit e iji wabidamak madoçizowin. Anicinabek kitci widjihahenimok kakina wiyaw kak aki kak acitc enigokwakimigak kijik kak. We dac ke abidjictcikadek kidji noswadamik mino madizowin kidji mayawik ka pakanagonan ka wawiyak makikiwinan: wiyaw, inimidjiwin, inenidamowin acitc tebenidjigewin. Anicinabek ogi manadjihawan kakina awesizan ka madjiwomiginak aki kak acitc aki inakonogewina ka kitci mane kitci mitaso midana pibonagagan.

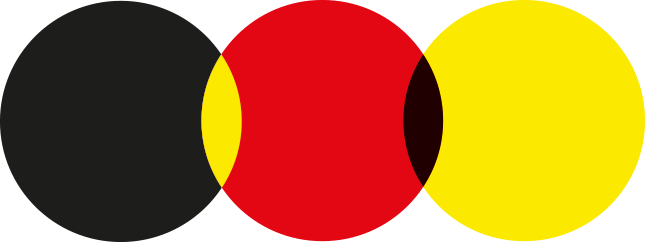

I am balance

“We walk on the snow, we travel with the help of snowshoes and canoes, across roots, we knew how to keep our balance and we are still standing.”

– Normand Kistabish

The medicine wheel, a symbol of our concept of life, expresses a balanced whole where everything is interrelated. The Anishinabek feel every fibre of their being intricately connected to the territory and linked to the universe. This model may serve as a guide to help us live a good life, by balancing its different aspects: physical, emotional, mental and spiritual. Respect for all living creatures and the laws of nature has supported the Anishinabek through the passage of time.

ADI E IKIDOMAGAK KIKINOHAMAGEWINAN KATAGOK KA WAWIHAK KAK?

Ka wawiyak tabadjimomagan adi e iji mamawi sigakosek ka pakanagogan modizowinan ka tagok aki kak. Mamawisinonan kakina madisowinan pepejik anicinabe (wiyaw, omidanendjigan, e inamidjiwotc e iji tebenidjigetc (o tebwetamowin). Pepejik ka tacik e inakamiziwik ki samickomin, kona kodigiwok, ka pecowamawik acitc kebi nabickogowik kid auanike pimatisidjik. Kakina dac e taciwik ki kipiwazomin kidji mamidinenimawik kodigiwok ka widji madizomawik kidji kewina kidji kacka mino ijigabwiwatc.

Midanendjigan kidji kackitowin kidji kikinohamaziwin, kidji nisitamiwin, kidji mamidinendamiwin, kidji kijigabidamin kidji nisitamin. Acitc ki midanendjigen ka iji mikomomagak. Acitc kidji kwikwadaziwin kidji mino inendamiwin kidji kacka mino madizowin kakina ke samickimin ka odji nikomowin acitc ke ibi ijitcigewin.

Wiyawin ki wiyaw win wedi, e iji mino madiziwin acitc ijinagoziwin. Adi kegin e iji madjitowin ki wiyaw ki mino madizowin kak kida nagon. Kidji mino madizowin, anicinabe panima kida mino todadizo, nisetc, madjibiwotc, anecimotc, wisinitc, minikwetc acitc kidji mino apenimotc. Acitc adi e iji tajiketc e ijinagonak, od akia di e iji manadjitowin. Aki dac e iji minwacik kegin dac minwacin, kicpin dac minwacik kin odji mojak aki kewin kida minwacina

Kije manidowin, o tebwetamowin: wedi win manidok, kin pidjiwi, kida tebwetamowinan, kida apitenidaowinanacitc ka iji kackitowin kidji kijenidamowin. Ki tebwetamowin odjibide ka iji tebwenidamiwik kidji mino inadiziwik acitc ke iji noswadamiwik inakonigewin mino madizowin odji. Ka ijitcikewik ayamiwinanan, ka iji pagosenidjigewik acitc ka kitci icpendagok kidji minkwenidamik adi keginiwit adi e iji tabine kipiwazowik, kidji manadjiyak kakina madizowinak, kida ayanike kimotcominanak acitc enigokwakimigak (kijik.)

Ka inimidjiwin, owe win ki odehi kak acitc adi e inamidjiwin kidji odapinimin ka iji pidjimidjiwin. Mic owe ke widjiwigowin kin tabine, kodigiwok mamawi acitc aki. Acitc kidji noswadaminin ka iji inadabidamiwin, ka iji inendamiwin,acitc panima kidji wabidamiwin acitc kidji minabidowin ki odehi kak ka atek acitc kid otcitcagoc kak,

*Ka endazinadegan acitc e ikidomigagan e ijinagozinaniwak, inendamowina, inimidjiwinan, acitc manitowina kawin pejigon ijinagosonon awiyegok acitc ijiwegiziwinan.

What do the teachings in the circle mean?

The circle symbolizes the link between the various forms of life that exist in this world. It encompasses the aspects of each human being’s life (physical, mental, emotional, spiritual). All of our actions influence us, others around us and future generations. We each have the responsibility to consider the others around us, to establish an egalitarian space where everyone has their place.

…the mental aspect is related to your ability to learn, understand, reflect, analyze, etc. It also refers to your psychological health, which in turn is connected to all the other components of your life and influences your decisions and actions.

…the physical aspect concerns your body, its state of health and its particularities. How you take care of your body will have an impact on your well-being. The well-being of human beings requires some basic needs; breathing, moving, resting, eating, drinking, and feeling safe. This aspect is also related to the physical environment, the territory and how you interact with it. Therefore, what’s good for aki is good for you, and what’s good for you is always good for the Earth.

…the spiritual aspect is the relationship with the spirit world, your inner world, your dreams, beliefs, values and creativity. Within spirituality lies our moral values and our true code of ethics. Ceremonies, rituals and the sacred are dimensions that remind us of our personal responsibilities, such as honouring all living creatures, our ancestors and the universe.

…the emotional aspect is the direct connection with your heart and the acceptance of the emotions you feel. It’s this relationship with yourself, with others and with the Earth. It’s about your commitment to your dreams, your intentions and the need to create opportunities to visualize and accomplish what’s in your heart and soul.

*The colours and meanings related to physical, mental, emotional and spiritual aspects may vary among individuals and nations.

© Frank Polson

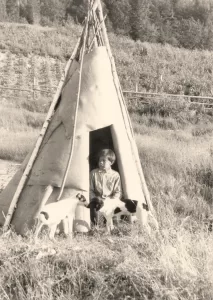

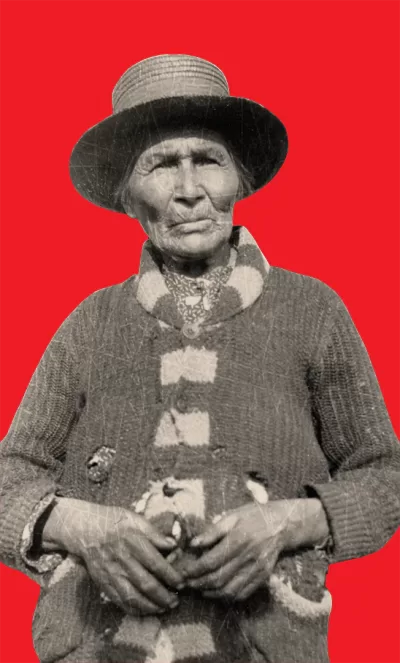

NIN AYANIKE > I am ancestral

NIN AYANIKE

« Ka sagitowan nid anicinabewin e mikadaman ni kacki wabidan adi nid ayanikek e kigitayindamotc. »

– Pinock Smith

Wecketc aji kitci oma kideman tcibwamici wabickiyek tagociniwatc ka kitci mane kitci mitaso midana pibonagagan. ka iji madizowik acitc kidinewinan padikisin aki kak. Anicinabe ijitawin adi kinwit e ojitowik e ijitcigewik adi gotc ke inabidek. Kid ayanikenanak ogo kakinenidamawanaban kicpic dac aga kikinenidamawatc omikanawaban ke todamawatc1. Ka tagok dac awe ka tanakigiwik ka iji madizowik ki pakanise tedago. Ka iji tebwetamik, ka iji ayamihawik ka iji noswadamik, ki madiziwinan, ka iji odiziwik, kida ijigewinan, ka inabidamiwik aki tedago ki meckodjisenon. Kid anicinabe kikinohagewinanan ka pagidinamowabik ki nidjaniciminanak kipakise, anic kidi ijigewinan, kid anicinabe ijitawinan acitc ki tebwetamiwinan kiginedamagoman (kid ayanike pimadizidjik) kitci anicinabek. (kokominanik ki mocominananik.) Kakina dac kigackitoman kidji madjitowik kagi nigadimagowik kidji kinendamik kidji tabibendamik. Kokom te nogom kidji widokagowik adi kid ayanike pimadizidjik kabi todamawatc. Kidi te na wabinak? Nogom dac kagwedjimadan kegona kidji nisitamik adi ka odji inenidamawatc kidji ocki ojitawatc ke inabidjitawatc kid ayanike pimadizidjik2.

- Richard Kistabish, 1987, p. 11

- IDEM

I am ancestral

“What I really appreciate about my culture, within my work, is that it allows me to appreciate the intelligence of my ancestors.”

– Pinock Smith

Our existence on the continent goes back thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans. Our way of life and our language are well rooted in the territory: “Culture refers to all our ways of doing things, whatever they may be. Our ancestors knew how to do things and when they didn’t, they invented1“. Our way of life has changed dramatically since colonization. Our rituals, our rights, our institutions, our economy, our language, our worldview have all undergone profound transformations. The transmission of our ancestral knowledge from one generation to the next has been interrupted, but our language, culture and spirituality have been preserved by our Elders. Together, we can revive this memory and reclaim our ancestors’ heritage: “Kokom is here today to help us inventory how our ancestors did it. Will she be here tomorrow? Let’s ask her now the questions that will help us understand how our ancestors invented2“.

Listen to Alice Jérôme

Listen to the singing of Marilyn Chevrier-Wills

Listen to the movie of Kevin Papatie

Listen to the whispers of a kokum

Listen to Grace Ratt

Listen to the whispers of a moshum

TIMELINE

NIN ANICINABEMOWIN

I am Anicinabemowin

KE IJINAMIK ANICINABEMOWIN KIDJI MADJIWOMIGAK

Kakone kisis 2019, kitci agidasin ki inendagon anicinabemowinanan pibon UNESCO kagi papamadjimototc owena. Minwashin ogi ojiton MIAJA Kebaowek kak, ki mawadjidinaniwan kidji anamikawadjigadek kid anicinabewinan acitc kid ijigewinan anicinabemowinan. Odakinak kigi kajigabidanan, nogom e ijinagok,acitc kigi kigi weniceman adi ke ijinagon anicinabemowin. Kigi mazinibihanan adi kabi ikidinaniwak kabi nijinigonak. Atwagan mazinadek, tabadjimomigan minigik ke mosemagak kidji madjihomagak kid ijigewinan ket ayanike pimatisidjikinan odji.

Ka tasogonogozitc 21 odehimin oma ka kitci piponak, Trudeau ogima ogi odapinan inakonigewina odji anicinabe ijigijewinanan kidji nisitawenindak Kanata anicinaben oda ijigijewinanan (owe inakonigewina 35 ka tasozinadek inakonigewin Ejidjikatek 1982 acitc tibadjimowin Mamawi otek anicinabek pagidenidazowinan). Owe inakonokewin, o nakwetan ka Kagwedewinanan indowin Midjitwewin tebwewin acitc koka gwayakondiwin, inendagozi kitci ogima kidji widokik acitc kidji pagidinak coniyana kidji kockobidogadenak, koka kidji kiwe odapinamowatc, kidji ganawenindamawatc acitc kidji eckam sogitowatc aninabe ijigijewinanan.

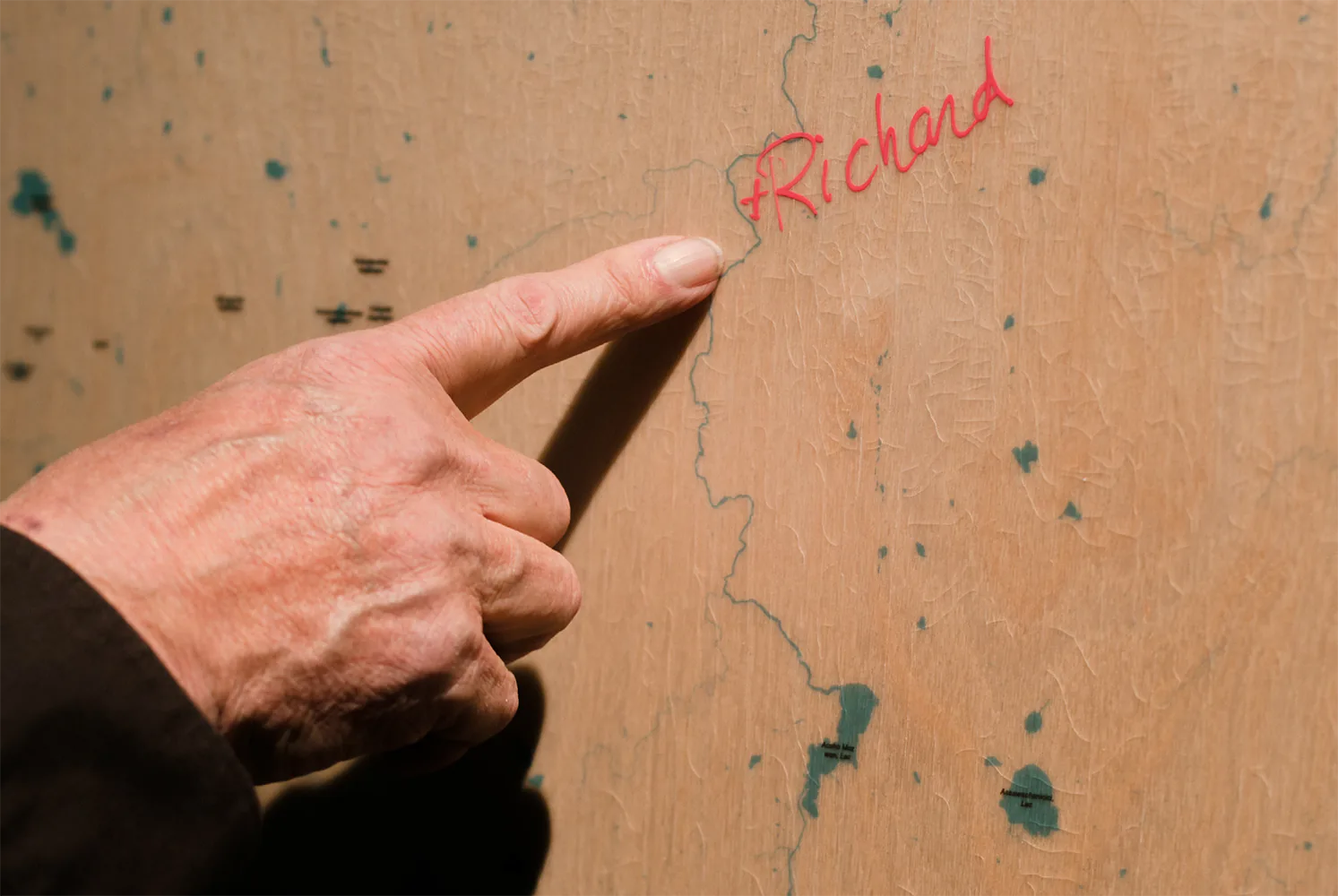

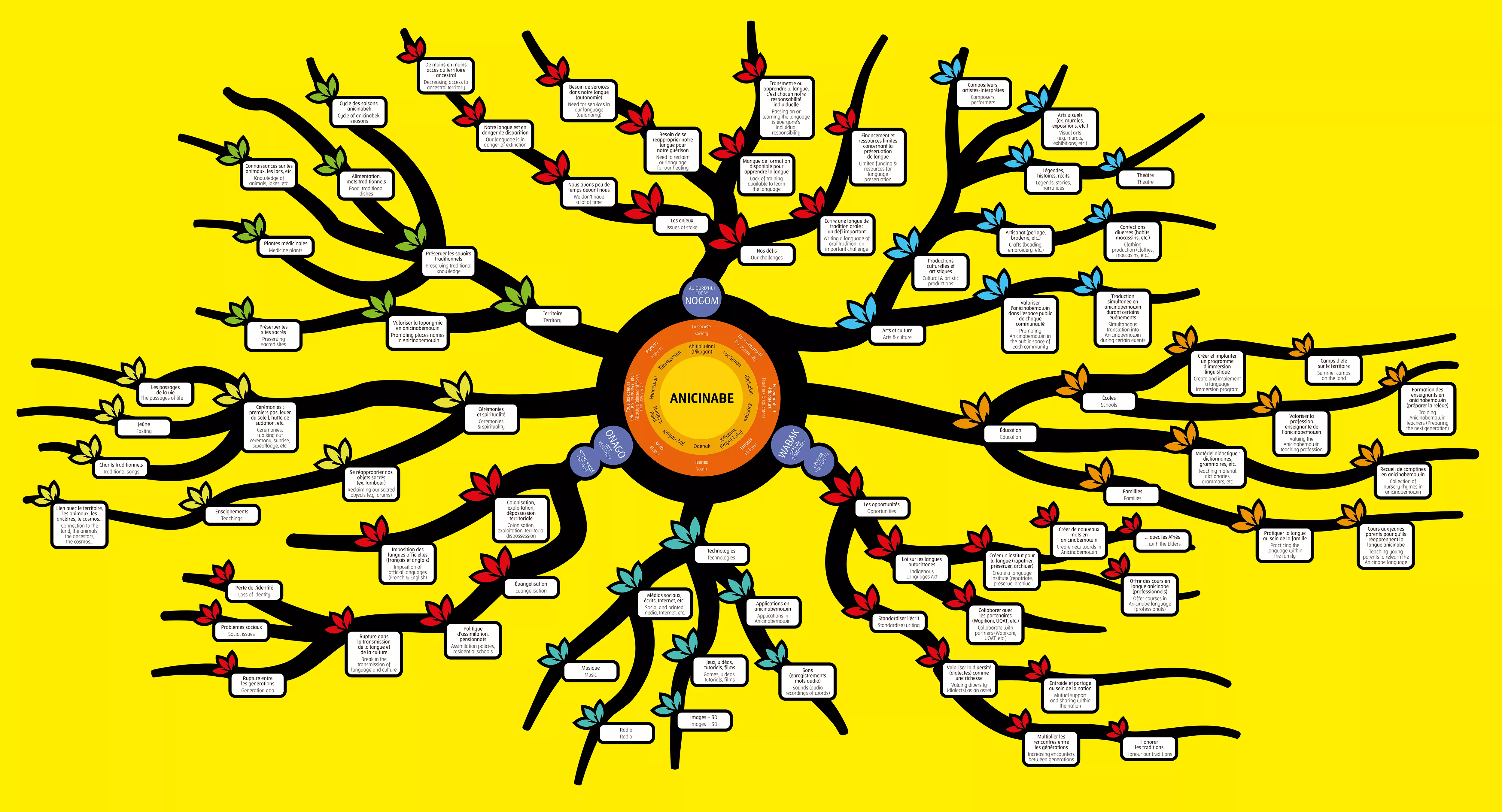

A collective vision of the future of Anicinabemowin

In September 2019, in recognition of the International Year of Indigenous Languages declared by UNESCO, Minwashin hosted the MIAJA event in Kebaowek, a gathering to celebrate our Anicinabe culture and language. Together, we reviewed the past, observed the present and reflected on shaping the future of Anicinabemowin. What we heard during these two days is here represented in pictorial form. This map details the path that we will have to follow to ensure the continuity of our language for future generations.

Furthermore, on June 21st of that year, the Trudeau government passed the Indigenous Languages Act to recognize the language rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada (under section 35 of The Constitution Act, 1982 and the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples by the United Nations). This Act, which responds to the “calls to action” by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, appeals to the Canadian government to support and fund projects to revitalize, reclaim, maintain and strengthen Indigenous languages.

NIN ANICINABEMOWIN

« Kitci cewiwan anicinabemowin kiga onitiman kid ijigijiwewinan, acitc kid anicinabewinan.Apinagotc dac kodak ijigijiwewin abidjitowik ki pakesidonanan adi e iji mamidenidamawinan pepejik edacik kidinenidazoman kidji madjitowik. Kakina dac ki tabinidazoman kidji madjihomagak kid anicinabemowinan. »

– Virginia Dumont

Anicinabe ijigijewin kitci apitenidagon kidji kinenidamik mi owe ka kidji ijiwegazik. Panima dac kiga anicinabemoman etaso kijigak kidji madjiwomagak kiniwit odji. Mojak kagwectok kidji anicinabemowek migwetc inenididan odji anicinabewin1. Kagi pijiwebazik kagi iji nackimik madizowin. Mojak anicinabe ogi apintenidan odijigijewin.

- Richard Kistabish, 1987, p. 15

I AM ANICINABEMOWIN

“Preserving our language is vital. It distinguishes us from others, it’s our identity. The Anishinabe language echoes what we have been through, what we have experienced. Try to speak it daily. Be grateful and proud.”

– Virginia Dumont

Anicinabemowin is in a state of great fragility and is in danger of dying out forever. Without it we no longer exist as a people: “Using only the language of the dominant culture, we leave aside our way of thinking1”. Its survival depends on each one of us, we’re all responsible for maintaining it alive.

ANICINABE OJIBIHAN KEGON KA SIGITOWIN KONA KEGON KA NABICKOGOWIN.

Write a word in the Anicinabemowin language that you like or that represents you.

MIDASI PIBON ENIGOKWAMAMIGAK ANICINABEMOWINAN ODJI

Anicinabe ijigijewinan midonenindamonaniwanan kidji mayadanagonan kikenidamowinanan kago ojiwomigak aji mane kitci mitasomidanan pibonigakan. Pepjigon dac anicibenabe ijigijewinan miya ka kitci apitenidagogan kakina awiyegok odji. (anicinabek towak humanite). Mane dac anicinabe aki kak, tagon pekan e ijigijewinan anicinabemowinan mi dac e odji pepejik apitci aniwenindagoziwatc. Kicpin dac wi apitenindamawin e pakanewatc owe Algonquin Pictures dictionary ijinikade kidji nitamin, anicinabek kitci ogimawin kagi ojitowatc.

Nanidam anicinabe aki kak, tedago cewiwon anicinabemowin. Nogom kawin napitc o nigiwak oda anicinabemosiwan onidjanisiwan. Tabiskotc kakina ancinabemowinan enigokwamamigak, ket ingi anicinabe ijigijewin kid I nanizanenindagwak.

« Oda apitenindan pejik anicinabemowin poninagon e taso nijin manactagak1. »

Aji kakandjihenidagon kidji madjitowik acitc kidji kockonomowik kid anicininabemowinan panoma dac pepjik oga atagon mikimowina. Ke 2022 ke madjisek midasi pibon enigokwamamigak anicinabemowinan ke notc ke mikidigadek dac anicinabek o pagidenidazowinan:

- kidji kacka tibenindazowatc ke ikidowatc (kidji anamatogoziwatc)

- kidji kacka kikinohamaziwatc od ijigijewinan

- kidki kacka kakina awec kidji anicinabemowatc2

An international decade for indigenous languages

Indigenous languages are systems of complex knowledge that have developed over thousands of years. Each of these languages is part of this invaluable wealth for humanity. Within the Anicinabe Nation, there are different dialects of Anicinabemowin, which makes each community unique. To appreciate the linguistic diversity, we invite you to consult the Algonquin Picture Dictionary application, developed by the Algonquin Anishinabeg Nation Tribal Council.

For certain communities, the state of the language is in a very fragile state. The transmission of Anishinabe language from parent to children is currently facing a serious decline. Like most Indigenous languages around the world, the future of Anicinabemowin is in peril:

“It appears that every two weeks an Indigenous language disappears.1”

The need for immediate action to preserve and revitalize the Anicinabemowin language has become urgent and everyone must do their part. The year 2022 will mark the beginning of the International Decade of Indigenous Languages, with a focus on the “Rights of indigenous peoples:

- freedom of expression

- education in their mother tongue

- participation in public life using their languages2”.

- (Ka nepadji kijabidamowatc anicinabewina mamawi otek, 2018) ; Instance permanente sur les questions autochtones des Nations Unies, 2018 ; United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, 2018

- Idem

KAGWEDEWINAN KIDJI INDOWIK (KONA ENDOTAMONANIWAN) KE PI MIDASI PIBONGAK :

Adi ke totamiwin kidji madizomigak anicinabemowin? Adi ke todamiwin kidji kacka anicinabemowatc anikobidjigananik?

Call to action for the next decade:

What are your intentions for safeguarding the future of the Anicinabe language? What action(s) do you plan to take to ensure the transmission of our language to future generations?

NIN ANICINABEK

We are anicinabek

NIN ANICINABEK

Mane e midasi pibonak ki inanokinaniwanan ki kibagade tewekan ki kickwehihagani. Aji dac midasi pibon, koka kigi nodawanan e mawadjidiwik. Tabickot tewekan, kidi ijigijewinan panima ke tanedomigak.

Anicinabek pazigwiwatc acitc ka waweyak madji wawijinamik aki tabickot weckat ki dinewinan kida pasesan kitci kitigan kaktabickot aki nigamowin. Aga nanagidjitowik, tewekan kiga nimiwigonan tabickot kitci pinecicak. Ozam koka kigi mackwiziman acitc ki minawaziman1.

We are anicinabek

For several decades, our ceremonies were banned and the tewekan was silenced. A few decades ago, we once again began to hear it at our gatherings. Just like the tewekan, the language must once again be heard:

When the people rise and the great circle begins to caress the earth like in the past, [our] words […] will resonate once again across the garden, like the song of the earth. Without even realizing it, the drum will make us dance like great birds. Because we’ll be strong and happy again1.

- Ejinagosi, 1986, p. 21

Listen to the music of the drum

Meegwetch